I think about the late 1960s a lot—probably more than most people.

Everything I know about the decade comes from films, documentaries, and secondhand stories. The cars, the culture, the music, the parties—the hippies. It all makes me wonder what it would have been like to step back in time, even just for a moment, to experience a world that seemed both freer and more innocent. A time when picking up a hitchhiker felt like an act of kindness rather than worrying at which milepost the murder was going to happen.

I won’t pretend to be an expert on the era—how could I be? I was born in the late ’70s and grew up in the neon glow of the ’80s.

Still, I’ve absorbed what I can through my mother’s stories, the media I’ve consumed, and a soundtrack unlike any other decade. And if there’s one thing I know for sure, it’s this: the ’60s had style—especially in its latter half.

From vibrant television shows to music that carried messages of hope, love, and peace—sometimes with a playful twist—the late ’60s had a style all its own. Fashion was both structured and rebellious: clean lines, sharp symmetry, yet softened by fringe and flared silhouettes. Architecture embraced the future, sleek and space-age. It was an era of bold ideas, often romanticized as simpler than it truly was, yet undeniably forward-thinking.

Growing up in the ’80s, my family’s massive Curtis Mathis TV flickered with reruns of The Monkees, The Patty Duke Show, I Dream of Jeannie, Bewitched, and Batman with Adam West.

On the other side of the room, my mother would hum along to Trini Lopez’s Lemon Tree as it spun on our Sears stereo turntable.

And from the back of the house, my dad’s acoustic guitar echoed through the walls—his at-home setlist always circling back to Kansas City.

I suppose my mild obsession with the late ’60s isn’t so different from my nieces rewatching films and TV shows from the ’90s. Nostalgia works in cycles. But I’d argue the ’60s stand apart—the fashion, the music, the cultural shifts. There was nothing quite like it.

By the time I graduated college in 2001, the golden age of ’60s media had started to fade. Nick at Nite wasn’t the same, and pop culture was shifting. But certain films still kept the era alive for me.

It wasn’t just old TV reruns or family stories that fueled my fascination with the late ’60s. Certain films and music made my imagination run wild, painting a version of the decade I wished I could step into.

That shift started when I saw That Thing You Do! The movie’s bright and amusing infectious energy made the era feel alive—the music, the innocence, the idea that a garage band could suddenly take over the airwaves without the worry of an algorithm. It felt like a world I wanted to be part of.

By the late ‘90s I was attending Arizona State University and my musical palette started to open up when my quirky roommate came home with a CD that showed a man wearing thick black-framed glassed posing on the cover like he was conducting an orchestra. His hair slicked back gave the vibe of I Dream of Jeannie’s Tony Nelson sipping on a cocktail in his futuristic living room.

The artist was Esquivel.

The music of Esquivel was music I had only heard on TV, but never realized someone actually sat down and made this music. While my roommate probably thought he was being ironic, I took Esquivel’s music more literal.

The moment those quirky, space-age arrangements filled the room, I felt like I had stepped into an episode of I Dream of Jeannie—doing my best to swoon Barbara Eden. It was weird, futuristic, and playful—like a sonic time machine. I fell in love instantly.

Whenever I needed a break from the rock music of the 2000s, I’d put on Esquivel, and suddenly, I wasn’t just in my college dorm room—I was in some imagined version of the 1960s, where everything was sleek, stylish, and effortlessly cool. This always brought me comfort.

As the years carried on, my obsession with the 1960s had waned, but that wasn’t until I discovered AMC’s Mad Men in 2007.

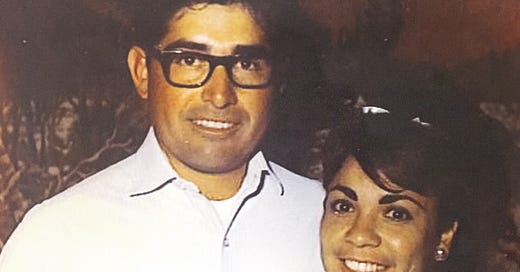

The series was set in the late 1950s and spent most of its time in the 1960s, depicting a world much like the one I had imagined from my mother’s photo albums. The only difference? My parents grew up in rural Arizona, while Don Draper lived in the heart of Manhattan, the embodiment of a polished, white-picket-fence existence.

Nevertheless, Don Draper’s demeanor reflected the attitudes of his era—many of which lingered well into the ’80s as I was growing up. He carried himself like a man who had all the answers, yet beneath the surface, he was merely projecting an illusion of control.

Watching the series, you realize Don wasn’t an advertising mastermind—he was a man making it up as he went along. And yet, somehow, he was good at it. That tension—between his carefully curated image and the chaos underneath—felt eerily familiar. The way men chain-smoked and drank at work? It wasn’t far off from the family parties I grew up with in the ’80s—except by then, the drinking had moved from the office to the home—or in my case, the garage that had a pool table.

But nothing made me fall harder for the ’60s than Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. He didn’t just depict the decade—he captured its essence, immersing us in 1969 as if we had stepped through a time portal. The film’s sets looked exactly like the homes I grew up in. The framed photos on coffee tables, the faded furniture, the sunlight streaming through sheer curtains—it was like being transported to my aunt’s pristine living room, where knickknacks sat carefully arranged around glass ashtrays.

And the soundtrack? That was something else.

Tarantino pulled real 1960s radio broadcasts from Los Angeles’ KHJ, complete with DJ banter, jingles, and live-read commercials. When I first listened to the soundtrack, it wasn’t just about the songs—it felt like tuning into lo-fi AM radio in 1969.

By 2020, the world had shut down. Days blurred together, and an eerie stillness settled over everything. I wasn’t as panicked as some, but like everyone, I was searching for something steady—something familiar to cling to. Somehow, the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood soundtrack became that anchor, transporting me to a world that felt warmer, simpler, and far removed from the COVID chaos.

I remember one day, in the middle of lockdown, asking my Google Home to play the soundtrack. I sat on the couch and closed my eyes, letting the music take over—no screens, no distractions, just my imagination running wild. As the KHJ deejay announced the weather report for L.A. before the next song, I pictured myself as a kid, dreaming of one day sitting behind a microphone, spinning records for an audience I couldn’t see but somehow felt connected to.

As the lo-fi crackle of old recordings filled my room, I felt like I was stepping back in time. It wasn’t just nostalgia for a time before smartphones; it was a realization—I could live without modern technology. I didn’t need a constant stream of notifications. I didn’t need to be connected 24/7. In that moment, the world felt simple again.

That moment didn’t last forever, of course. The world eventually reopened, and it felt like people couldn’t wait to abandon simplicity.

Sure, you could find traces of that same physicality from the ’60s all the way into the early 2000s—before everything became digital, disposable, and effortless. But there was something different about the ’60s. It wasn’t just a decade; it was a way of life—an era where the romance of living wasn’t just felt, but created in the friendships and communities people built.

We live in a world without intention or effort. A world where connection is instant but more often than not, hollow. Where charisma has been replaced by curated profiles and conversations reduced to blue and gray bubbles—and sometimes green too. 😆 Where once, you had to rely on charm before touchscreens—your words, your presence, your sincerity proved your character.

Back then, effort mattered.

I see it in the love letters my parents wrote to each other when my dad attended electronics school after high school—each envelope a reminder that connection wasn’t always instant, but it was real. It was committed.

And maybe, despite all of our modern conveniences, we’re still searching for something that doesn’t disappear the moment we close an app.

Share this post